Review of Title V Maternal and Child Health Addressing Disparities

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic along with the growing racial justice movement have highlighted longstanding disparities in health and health care for people of color, including stark disparities in maternal and babe health. Despite continued advancements in medical care, rates of maternal mortality and morbidity and pre-term birth take been ascension in the U.S. Maternal and baby mortality rates in the U.S. are far higher than those in similarly big and wealthy countries, and people of color are at increased chance for poor maternal and infant health outcomes.i This issue brief provides an overview of racial and ethnic disparities across selected measures of maternal and infant health. It is based on KFF assay of publicly available data on CDC WONDER and the 2018 American Community Survey. While this brief focuses on racial/ethnic disparities in maternal and infant health, broad disparities also exist across other dimensions, for example, and there is pregnant variation in some of these measures across states and disparities within rural communities.

Racial Disparities in Maternal and Babe Wellness

Maternal Bloodshed Rates

Approximately 700 women dice in the U.Southward. each twelvemonth as a result of pregnancy or its complications.2 Pregnancy-related deaths are deaths that occur within one yr of pregnancy. Approximately one 3rd occur during pregnancy, over half (56%) occur during labor or inside the start calendar week postpartum, and another 13% occur betwixt six weeks and one year,3 underscoring the importance of access to health care beyond the period of pregnancy. Due to variations in reporting and data collection, it is possible that the number of pregnancy-related deaths is underestimated, and that the maternal mortality rate is much higher.4 , 5

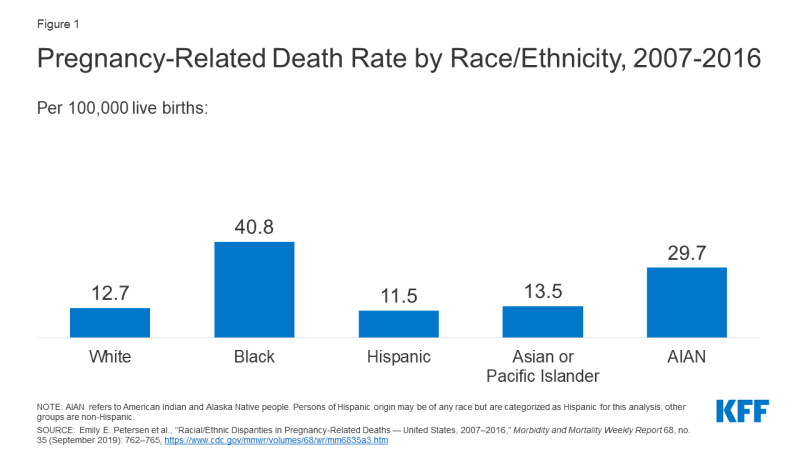

Black and AIAN women take higher rates of pregnancy-related deaths compared to White women. Black and AIAN women have pregnancy-related mortality rates that are over three and two times higher, respectively, compared to the rate for White women (40.8 and 29.7 vs. 12.7 per 100,000 live births) (Effigy one). This disparity persists even in California, where maternal mortality rates are lower than the national boilerplate and have been on the decline; yet, the charge per unit is more than than three times college among Black women compared to White women.6 There were small differences in the charge per unit pregnancy-related death between Asian and Pacific Islander and White women (13.5 vs. 12.seven per 100,000), and the rate for Hispanic women was lower compared to that of White women (11.5 vs. 12.seven per 100,000). These findings may mask underlying differences in subgroups of these populations.7 Farther, other enquiry as well shows that Black and Hispanic women are at significantly college risk for severe maternal morbidity, such equally preeclampsia, which is significantly more common than maternal death.eight , nine

Figure 1: Pregnancy-Related Decease Rate by Race/Ethnicity, 2007-2016

Disparities in pregnancy-related deaths for Black and AIAN women increase past maternal historic period and persist across education levels. For instance, the rate for Black women between ages 30 to 34 widens to over iv times higher than the charge per unit for White women (48.half dozen vs. 11.iii per 100,000), while the rate for AIAN women in the aforementioned age group is nigh four times equally high as the rate for White women (41.2 per 100,000.10 Further, racial disparities persist across teaching levels. Among women with a college education or higher, Blackness women have an over 5 times higher pregnancy-related bloodshed charge per unit compared to White women. Notably, the pregnancy-related bloodshed rate for Blackness women with a completed higher education or college is ane.six times higher than the rate for White women with less than a high schoolhouse diploma.eleven

Most pregnancy-related deaths are considered preventable. Cardiovascular conditions are the leading crusade of pregnancy-related death among women overall, highlighting the importance of care for chronic conditions on pregnancy-related outcomes. In that location are some differences in the leading causes of pregnancy-related expiry past race and ethnicity. In a study of pregnancy-related deaths during 2007 to 2016, cardiomyopathy, pulmonary embolism, and high blood pressure level were associated with a higher share of pregnancy-related deaths amidst Black women compared to White women and a higher share of pregnancy-related deaths among AIAN women were associated with hemorrhage and high claret pressure compared to White women. Hemorrhage, amniotic fluid embolism, and cerebrovascular accidents were associated with a higher share of pregnancy-related deaths amid Asian and Pacific Islander women compared to White women and hemorrhage and hypertensive disorders were associated with a higher share of pregnancy-related deaths among Hispanic women compared to White women.12

Nascency Risks and Outcomes

Blackness, AIAN, and NHOPI women are more likely to take certain birth risk factors that contribute to infant mortality and can have long-term consequences for the concrete and cerebral health of children. Preterm birth (birth before 37 weeks gestation) and low birthweight (divers every bit a baby built-in less than 5.five pounds) are some of the leading causes for babe mortality. Not receiving pregnancy-related care until belatedly in a pregnancy (defined as starting in the 3rd trimester) or not receiving whatsoever pregnancy-related care at all can besides increase gamble of pregnancy complications since early and regular prenatal care is important for monitoring wellness, managing existing medical conditions, and sharing health information. Black, AIAN, and NHOPI women have higher shares of preterm births, low birthweight births, or births for which they received late or no prenatal care compared to White women (Effigy 2). Notably, NHOPI women are five times more likely than White women to not brainstorm receiving prenatal care until the third trimester or to no receive any prenatal care at all (20% vs. iv%). Hispanic women too are twice every bit likely compared to White women to have a birth with tardily or no prenatal care compared to White women (eight% vs. 4%).

Figure 2: Percent of Births with Selected Chance Factors past Race/Ethnicity, 2018

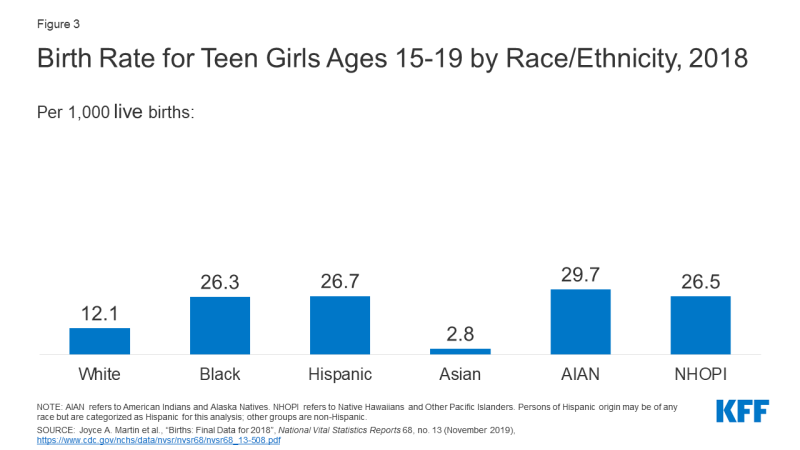

Teen nascence rates are college among Blackness, Hispanic, AIAN, and NHOPI teens compared to their White counterparts (Figure 3). In dissimilarity, the nascence rate among Asian teens is lower than the rate for White teens. Pregnant teens may be less probable to receive early and regular prenatal intendance. Teen pregnancy also is associated with increased chance of complications during pregnancy and delivery, including preterm birth.13 Teen pregnancy and childbirth can also have social and economic impacts on teen parents and their children.14

Effigy iii: Nativity Rate for Teen Girls Ages 15-19 by Race/Ethnicity, 2018

Reflecting these increased risk factors, infants built-in to women of color are at higher risk for bloodshed compared to those born to White women. Babe bloodshed is divers equally the death of an baby within the first year of life, only most cases occur within the first month after birth.15 The primary causes of infant mortality are nascency defects, preterm nascence and low birthweight, maternal pregnancy complications, sudden infant decease syndrome, and injuries.16 Infants built-in to Blackness and NHOPI women are over twice equally likely to die relative to those born to White women (x.8 and ix.iv vs. 4.vi per 1,000), and the mortality rate for infants built-in to AIAN women (8.2 per 1,000) is nigh twice as high (Figure iv). The mortality rate for infants born to Hispanic mothers is similar to the rate for those born to White women (4.nine vs. 4.vi per i,000), while infants born to Asian women have a lower bloodshed charge per unit (3.half-dozen per i,000). Data besides show that fetal death or stillbirths—that is, pregnancy loss later on twenty-calendar week gestation—are more common amidst Blackness women compared to White and Hispanic women. Moreover, causes of stillbirth vary past race and ethnicity, with higher rates of stillbirth attributed to diabetes and maternal complications amongst Black women compared to White women.17

Figure iv: Infant Mortality Rate by Maternal Race/Ethnicity, 2018

Factors Driving Disparities in Maternal and Infant Health

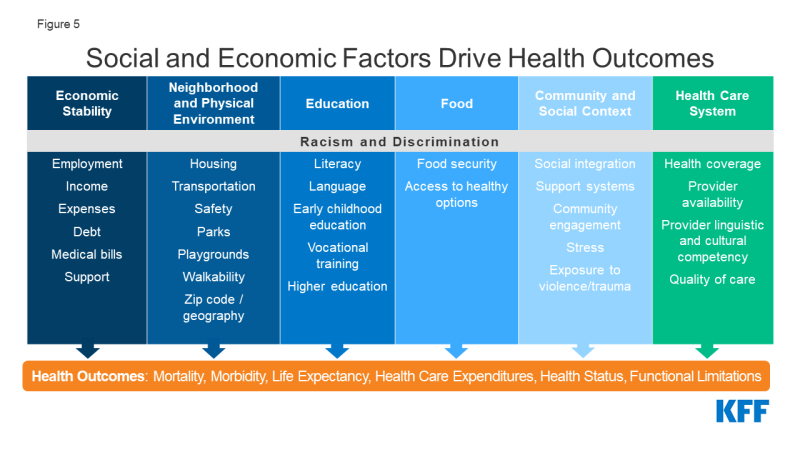

The factors driving disparities in maternal and infant health are complex and multifactorial. They include differences in health insurance coverage and access to care. However, broader social and economical factors and structural and systemic racism and discrimination, also play a major role in shaping health and disparities in health (Effigy 5). In maternal and babe health specifically, the intersection of race, gender, poverty, and other social factors shapes individuals' experiences and upshot. Recently in that location has been broader recognition of the principles of reproductive justice, which emphasize the role that the social determinants of health and other factors play in reproductive wellness for communities of color. Notably, Hispanic women and infants fare similarly to their White counterparts on many measures of maternal and infant health despite experiencing increased access barriers and social and economic challenges typically associated with poorer wellness outcomes. Research suggests that this finding, sometimes referred to as the Hispanic or Latino health paradox, in role, stems from variation in outcomes amid subgroups of Hispanic people past origin, nativity, and race, with better outcomes for some groups, especially recent immigrants to the U.S.18 However, the findings notwithstanding are not fully understood.

Effigy v: Social and Economic Factors Bulldoze Wellness Outcomes

Disparities in maternal and infant wellness, in part, reflect increased barriers to care for people of color. Enquiry shows that coverage before, during, and after pregnancy facilitates access to care that supports healthy pregnancies, too as positive maternal and baby outcomes subsequently childbirth. Overall, people of colour are more than likely to be uninsured and confront other barriers to care. Medicaid helps to fill up these coverage gaps during pregnancy and for children. However, women of colour are at increased risk of existence uninsured prior to their pregnancy and many lose coverage at the end of the 60-day Medicaid postpartum coverage period. Across health coverage, people of color face other increased barriers to care, including limited admission to providers and hospitals and lack of access to culturally and linguistically appropriate care.19 These challenges may be particularly pronounced in rural and medically underserved areas. For example, research suggests that a rise in closures of hospitals and obstetric units in rural areas has a disproportionate impact in communities with larger shares of Black patients.twenty

Research besides highlights the role historic and ongoing racism and discrimination play in driving racial disparities in maternal and infant health. Enquiry has documented the impact of social determinants, racism, and chronic stress on maternal and baby health outcomes, including higher rates of perinatal depression and preterm birth among African American women and college rates of mortality among Black infants.21 , 22 , 23 In recent years, research and news reports accept raised attention to the effects of provider discrimination during pregnancy and commitment. News reporting and maternal mortality case reviews have chosen attention to a number of maternal deaths and near misses amidst women of color where providers did non or were slow to mind to patients. In one report, Indigenous, Hispanic, and Blackness women reported significantly college rates of mistreatment (such as shouting and scolding, ignoring or refusing requests for help) during the class of their pregnancy.24 Even decision-making for insurance status, income, age, and severity of conditions, people of color are less probable to receive routine medical procedures and experience a lower quality of care.25 One recent study of infirmary births in Florida establish that in that location were meaning improvements in mortality for Black newborns who were cared for by Black physicians, pointing to the importance of culturally competent care.26 A recent KFF/The Undefeated survey likewise found that most Black adults believe the health intendance system treats people unfairly based on their race, and one in five Black and Hispanic adults report they were personally treated unfairly considering of their race or ethnicity while getting wellness intendance in the by year, with a college share of Black mothers reporting unfair treatment. Black adults besides were more likely than White adults to report feeling a provider didn't believe they were telling the truth and being refused a exam, treatment, or pain medication they idea they needed.

Looking Ahead

Together these data show that racial disparities in maternal and infant health persist. Improving maternal and infant wellness is key for preventing unnecessary illness and death and advancing overall population wellness. Recent research finds that as many as 60% of all maternal deaths in the U.Due south. are preventable and that increasing access to preconception, prenatal, and interconception care tin reduce pregnancy-related complications.27 Salubrious People 2030, which provides ten-year national health objectives, identifies the prevention of pregnancy complications and maternal deaths and improvement of women's wellness before, during, and afterwards pregnancy equally a public wellness goal.

Reducing rates of disparities in preterm birth and low birthweight and eliminating racial disparities in these measures have been the focus of a national and local initiatives from clinicians and policymakers. Growing recognition of disparities has prompted efforts from clinical groups and public health officials to get more than informed nearly and accost their biases, practice shared decision making, and listen to and act upon the concerns of pregnant and postpartum patients peculiarly in urgent situations. In improver, a number of initiatives are underway through Medicaid to improve maternal and infant wellness and reduce disparities given the substantial part the plan plays in covering low-income children and pregnant women and, peculiarly, low-income children and pregnant women of color.

Looking ahead, the COVID-19 pandemic further highlights the urgency and importance of addressing disparities wellness more broadly and brought new attention to those disparities in maternal and infant health specifically. Information show that people of color are bearing a disproportionate burden of COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths, and may face increased barriers to admission testing. People of color also are facing significant economic impacts as a upshot of the pandemic, and are more probable than White people to report problem affording nutrient, housing, utilities, credit carte bills, or health intendance expenses due to COVID-19. The asymmetric cost of the pandemic on communities of colour has reportedly prompted more interest amongst pregnant people, specially people of color, to consider births outside of the hospital. While much remains unknown about the full bear upon of COVID-xix on pregnant women and their children, the CDC is collecting and publishing weekly pregnancy data to meliorate understand COVID-xix during pregnancy. Inquiry studies are also examining the impact of the COVID pandemic on pregnancy with a focus on people of color. Overall, prioritizing equity in pandemic relief and response efforts and in health more broadly volition be key to preventing the widening of disparities going frontwards and supporting progress in advancing maternal and babe health.

Source: https://www.kff.org/report-section/racial-disparities-in-maternal-and-infant-health-an-overview-issue-brief/

0 Response to "Review of Title V Maternal and Child Health Addressing Disparities"

Post a Comment